Hello Microbit

March 28, 2015 at 07:38 PM | categories: C, microbit, arduino, BBC R&D, blockly, work, BBC, C++, microcontrollers, python, full stack., full stack.D, webdevelopment, mbed, kidscoding | View CommentsSo, a fluffy tech-lite blog on this. I've written a more comprehensive one, but I have to save that for another time. Anyway, I can't let this go without posting something on my personal blog. For me, I'll be relatively brief. (Much of this a copy and paste from the official BBC pages, the rest however is personal opinion etc)

Please note though, this is my personal blog. It doesn't represent BBC opinion or anyone else's opinion.

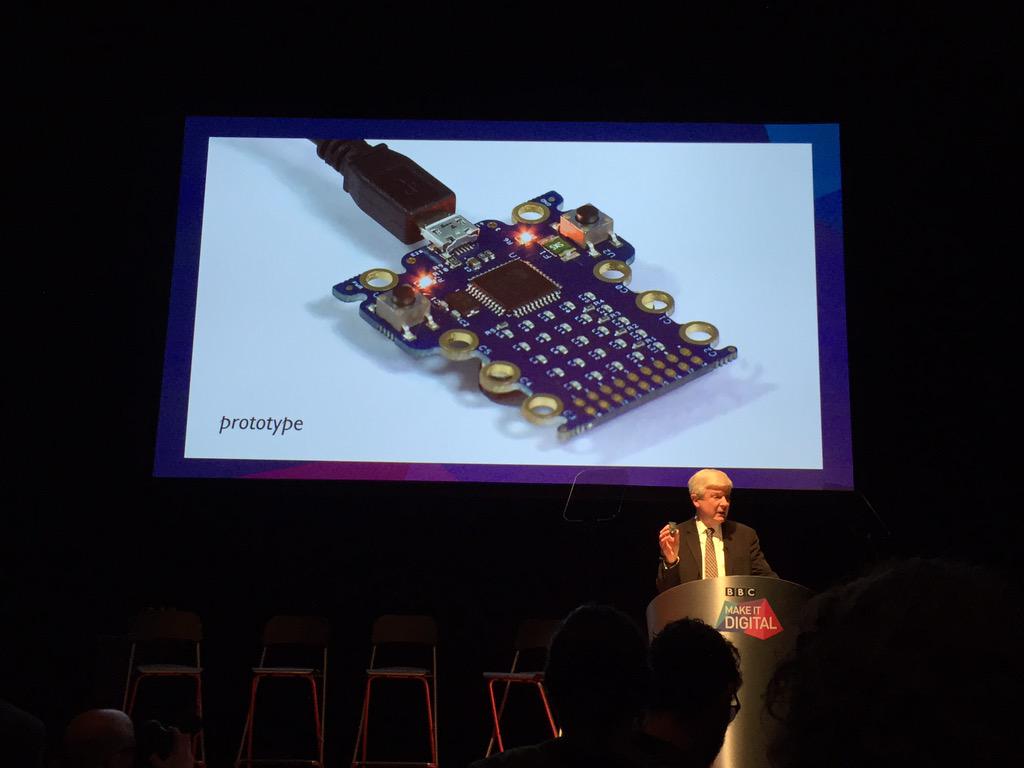

Just over 2 weeks ago, the BBC announced a small device currently nicknamed the BBC Micro Bit. At the launch event, they demonstrated a prototype device:

The official description of it is this:

BBC launches flagship UK-wide initiative to inspire a new generation with digital technology

The Micro Bit

A major BBC project, developed in pioneering partnership with over 25

organisations, will give a personal coding device free to every child in year 7 across the country - 1 million devices in total.

...

Still in development and nicknamed the Micro Bit,* it aims to give children an exciting and engaging introduction to coding, help them realise their early potential and, ultimately, put a new generation back in control of technology. It will be distributed nationwide from autumn 2015.... The Micro Bit will be a small, wearable device with an LED display that children can programme in a number of ways. It will be a standalone,

entry-level coding device that allows children to pick it up, plug it into a computer and start creating with it immediately.

...

the Micro Bit can even connect and communicate with these other devices, including Arduino, Galileo, Kano and Raspberry Pi, as well as other Micro Bits. This helps a child’s natural learning progression and gives them

even more ways of expressing their creativity.

...

Early feedback from teachers has shown that it encourages independent learning, gives pupils a strong sense of achievement, and can inspire those who are not usually interested in computers to be creative with it.

For me, the key points about the prototype:

- Targetted at children, and their support networks (teachers, parents etc). This is reflected throughout the system. It doesn't underestimate them though. (I work with cubs and scouts in my spare time, and I know they're much willing to try than adults - which means they can often achive more IMO. Especially at scout age)

- Small programmable fun device, instant feedback, with lots of expansion capability with a gentle gradual curve.

- Web based interfaces for coding, as well as offline interfaces

- Graphical, python or C++ code running on the device

- Designed to work well with other things and hook into larger eco-systems where there's lots of users.

(That's all public information, but for me those are really the key points)

Aside from the obvious -- why did the announcement excite me? Simple: While it wasn't my vision - it was Howard Baker's and Jo Claessen's, I implemented that Microbit prototype and system from scratch. While an earlier iteration had been built and used at events, I was asked to build a prototype we could test in schools and to take to partners to take to scale. (I couldn't work from that earlier iteration, but rather worked from the source - Howard and Jo. It was a harder route, but rewarding)

For those who recognise a similarity between this and Dresscode which I blogged about last summer, the similarities you see are co-incidental. (I was clearly on the same wavelength :-) ) While Microbit was in a early stage pre-prototype phase there, I hadn't seen it.

My thinking behind Dresscode though, was part of the reason I jumped at the chance to help out. It also mean though that some aspects I had a head start on though, and in particular, the IOToy and Guild toolsets I developed previously as part of some IOT work in R&D came in handy in building the prototype.(That and the fact I've used the arduino toolset a fair amount before)

Anyway, as I say, while I can't say much about the project, but it was probably the most intense development project I've worked on. Designing & building the hardware from scratch, through to small scale production manufacture in 3 months, concurrent with building the entire software stack to go with it - compilation toolchains, UIs and so on, AND concurrent with that was the development of detailed documentation and specs for partners to build upon. Intense.

In the last month of core development I was joined by 2 colleagues in R&D (Matt Brooks and Paul Golds) who took my spike implementations of web subsystems and fleshed them out and made them work the way Howard and Jo wanted, and the prototype hardware sanity checked and tweaked slightly by Lawrence Archard. There was still a month of development after that, so it was probably the most intense 4 months of development I've ever done. Well worth it though.

(Regarding names, project names change a lot. While I was building our device in even that short 3 months, it got renamed several times, and since! Don't read too much into names :-) Also, while it does fit anywhere else, it was Fiona Iglesias who was the project manager at the time who asked me if I could do this, and showed a great leap of faith and trust when I said "yes" :-) Balancing the agile process I needed to use against the BBC being very process driven (by necessity) was a thankless task!

Finally some closing things. On the day of the launch I posted a couple of photos in my twitter feed, which I'll repeat here.

The first was my way of going "yay". Note the smiley bit :-)

So, look what I made! http://t.co/OTCn14YN7s Earlier revs were built on my kitchen table :-) pic.twitter.com/2k9a2UBOZh

— Michael (@sparks_rd) March 12, 2015The second related to an earlier iteration:

Earlier iteration: pic.twitter.com/bmQ2G7KK2t

— Michael (@sparks_rd) March 12, 2015Anyway, exciting times.

What happens next? Dunno - I'm not one of the 25 partners :-)

The prototype is very careful about what technologies it uses under the hood, but then that's because I've got a long history of talking and writing about about why the BBC uses, improves and originates open source. I've not done so recently because I think that argument was won some time ago. The other reason is because actually leaving the door open to release as open source is part of my job spec.

What comes next depends on partners and BBC vagaries. Teach a child to code though, and they won't ever be constrained by a particular product's license, because they can build their own.

Anyway, the design does allow them to change the implementation to suit practicalities. I think Howard and Jo's vision however is in safe hands.

Once again, for anyone who missed it at the top though, this is a personal blog, from a personal viewpoint, and does not in anyway reflect BBC opinion (unless coincidentally :).

I just had to write something to go "Yay!" :-)

Connected Studio - Coding For Teens, Building the Dresscode

July 23, 2014 at 03:13 AM | categories: wearables, arduino, programming, iot, BBC, kidscoding | View CommentsAt a connected studio Build Studio last week, I along with 2 others in Team Dresscode prototyped tools for an proposition based around wearable tech. We worked through the issues of building a programmable garment, a programmable accessory, and a web app designed for teaching the basic of programming garments and accessories in a portable fashion.

We achieved most of what we set out to achieve, and the garment (as basic as it was) and accessory (again very basic) had a certain "I want one" effect of a number of people, with the web app lowering the barrier to producing behaviours. It was a very hectic couple of days, but as a result of the two days it's now MUCH clear as to how to make this attractive to real teenagers, rather than theoretical ones - which is a bonus.

Probably the most worthwhile thing I've done at work at the BBC in fact and definitely this year - beyond sending a recommendation to people in strategy last summer regarding coding.

The rest of this post covers the background, what we built, why we built it and an overview of how.

NOTE Just because I work in BBC R&D does NOT mean this idea is something the BBC will work on or take on. It does NOT mean that the BBC approves or disapproves of this idea. It just means that I work there, and this was an idea that's been pitched. Obviously I believe in the idea and would like it to go through, but I don't get to decide what I do at work, so we'll see what happens.

The only way I can guarantee it will go through is if I do it myself - so it's well worth noting that this work isn't endorsed by the BBC - I "just" work there

Connected What?

So, connected studio - what is that then?

Connected Studio is a new approach to delivering innovation across BBC Future Media. We're looking for digital agencies, technology start-ups and individual designers and developers (including BBC staff) who want to submit and develop ideas for innovative features and formats.

Note that this process is open to both BBC staff and external. It's a funded programme that seeks to find good ideas worth developing, and providing seed funding to test the ideas and potentially take forward to service. People can arrive in teams or form teams at the studio.

Connected Why?

And what was the focus for this connected studio?

- Inspiring young people to realise their creative potential through technology

- We want to inspire Britain's next generation of storytellers, problem solvers and entrepreneurs to get involved with technology and unlock the enormous creative potential it offers

- The challenge in this brief is to create an appealing digital experience with a coding component for teenagers aged 13-16

- Your challenge is to make sure we inspire not just teenagers in general, but teenage girls aged 13-16 in particular ** Ideally, we're looking for ideas that appeal to both boys and girls, however, we're particularly keen to see ideas that appeal to girls.

The early stages involve a idea development day - called a Creative Studio. At this stage people either arrive with a team and some ideas and work them up in more detail on the day, or arrive with an idea they have the core of and are looking for people to help them work up the idea, or people simply interested in finding an idea they think is worth working on.

That results in a number of pitches for potential services/events/etc the BBC could take forward. Out of these a number are taken forward to a Build Studio.

What happened on the way to the Build Studio?

So, that's the background. I signed up for the studio because I was interested in joining a team and interested in working with people outside our department - with a grounding either in BBC editorial and/or an external agency's viewpoint. I also had the core of an idea with me - which I'll explain first.

A meeting the previous week an attendee asked the question "If the stereotype of boys is that they're interested in sports, what's the stereotype for girls?". The answer raised by another person there was "fashion". Now, if you're a lady reading this who says "don't be so sexist, I'm not interested in fashion", please bear in mind I don't like sports - things like the commonwealth games, olympics, world cup, etc all leave me cold. Also please bear in mind the person asking the question was a lady herself, and the answer came from another lady at the meeting.

Anyway, true or false, that idea mulled with me over the weekend - with me wondering "what's the biggest possible draw I can think of regarding fashion?". Now the closest I get to fashion is watching Zoolander, so I'm hardly a world authority. Even I know about London Fashion week.

So, the idea I took with me to the creative studio was essentially wearable tech at london fashion week. I'd fleshed out the idea in my head more like this:

-

The BBC hosts an event at London Fashion week regarding wearable tech - with the theme of costumes for TV - which widens it beyond traditional fashion to props and so on. So you can have the light up suits and dresses but also props like wristbands, shoes, animatronic parrots, and so on. (Steampunk pirate?)

-

Anyone and everyone can attend, BUT the catch is they must have created a piece of wearable tech to take to the event - if they do however, they can take their friends with them, and one of them - either themselves or their friends can wear it down the catwalk.

To support this, you could have a handful of TV programmes and trails leading up to this, a web app for designing and simulating garments/etc of your choice, tutorials for how to build garments, and in particular allow transferable skills between the web app to creating programmable garments. So the TV drives you to the web, which drives you to building something, which drives you to an event, which drives you onto TV.

Now at the creative studio, there's essentially a "I've got this kind of idea" wall first thing in the morning - where if you've got an idea you can stand in front of those interested in joining a team and describe the idea- and then say what sort of skills/etc that you're after.

In my case I described the above idea, and said that I was primarily looking for people with an editorial or business oriented perspective. After all, while the above sounds good to me, I was never a teenage girl, and lets face it I was in the geeky non-cool demographic when I was a teenage boy :-) First person who joined me was Emily who has worked on various events at the BBC, primarily in non-techie areas including Radio 1's Big Weekend, Ben from a digital Agency and Tom from Nesta - a great mix of people. Thus formed Team Mix.

Team Mix's refined idea

We worked the idea through the day - with every element up for grabs and reshaping. The idea of being limited to London Fashion week was changed to be the wider set of possibilities - after all the BBC does lots of events from real physical ones like Radio 1 Big Weekend, through glastonbury, the proms, Bang goes the theory, through to event TV including things like The Voice.

After a session with a member of the target audience, we realised that while the idea was neat, for a teenager asking them to build something for a catwalk is actually asking an awful lot. Yes, while showing off, and finding your own identity is a big thing, not losing face, and not doing something to lower your status is a real risk. "I couldn't make that". As a result, we realised that this could be sidestepped by whatever the event was being changed to "this is a collection of your favourite stars wearing these programmable outfits and you get to decide what and how those clothes behave". However, on the upside this made the web element much clearer and better connected.

It left the accessories part slightly less connected, but still the obvious starting point for building wearable tech. This left the idea therefore as a 3 component piece:

-

Celebs with outfits that are programmable - a trend that seems to be happening anyway, and these would be worn at some interesting/cool event - to be decided in conjunction with a group running interesting/cool events :-)

-

A website for creating behvaiours via simple programming - allowing people to store and share their behaviours - the idea being that they control the outfits the celebs will wear.

-

Tutorials for building wearable tech accessories - which are designed to be programmed using the same behaviours as the celeb outfits - making the skills transferable.

So the idea was pitched at the creative studio - and ours got through to the Build Studio stage.

Taking wearable tech to the Build Studio

Out of the 20-30 ideas pitched, it was one of 9 to get through to the build studio. However, another team had ideas related primarily to Digital Wrist Bands, and our team - Team Mix - was asked to join with theirs - Team DWB - resulting the really non-sexy name Team Mix/DWB. That mean 8 teams at the studio. One of the teams didn't show, meaning 7 builds.

It transpired that out of the two teams, only myself and Emily could make it to the build studio - so we chatted to Ben and Tom about what they'd like to see achieved, and also to those on Team DWB. The core of their idea was complementary to our accessories idea so we decided to focus that part of our build on wristbands.

So, what was our ambition for the Build Studio? The ambition was pretty much to do a proof of concept across the board, and to describe the audience benefits in clearer, concrete terms. Again, there was the opportunity to bounce the ideas off a couple of teenagers.

We had help from the connected studio team in seeking assistance from other parts of FM, and after a call across all of BBC R&D, various groups in FM across the north and south we had a volunteer called Tom who was a work placement trainee.

I also ran our aspiration for the build studio via Paul Golds at work, and asked him if he wanted to be involved, and in particular what would be useful, and while he couldn't make it to the Build Studio, he did provide us we simple controllable web object.

What we built at the Build Studio

So the 3 of us set out to build the following over the 2 days of the build studio:

-

A wearable tech garment, which mirrors a web app, and in particular has a collection of programmable lights.

-

A web app for allowing a user to enter a simple program to control a representation of a web garment, with increasing levels of complexity. The app demonstrated implicit repetition, as well as sequence and selection.

-

A bracelet made of thermoplastic with programmable behaviours controlling lights on the device, perhaps incuding feedback/control using an LDR.

And that's precisely what we built.

The wearable garment was built as follows:

-

LEDs were sewn in strips - 8 at a time - onto felt. Conductive thread then looped through and tied on as positive and negative rails - like you would with a breadboard. Then attached underneath the garment so that the lights shone through.

-

The microcontroller for the garment was a Dagu Mini - which is a simple £10 device which is also REALLY simple to hook up to batteries and bluetooth. I've used this for building sumobots with/for cubs too. It's able to take a bit of bashing.

-

For each strip, the positive "rail" was connected to a different pin directly on the microcontroller - not necessarily the best solution, but works quite well for this controller.

-

Code for this was really simple/trivial - simple strobing of the strips. The real system would be more complex. In particular this is the sort of code in pastebin

However, the "real" garment would use something like this iotoy library for control - to allow it to be controlled by bluetooth and also by an IOT stack.

The web app is a simple client side affair only, and uses a small simple DSL for specifying behaviours. This is then transformed into a JSON data structure for evaluation. This uses jquery, bootstrap, and Paul's awesome little web controllable light up dress. You can see this prototype on my website.

Again, bear in mind that this is a very simple thing, and the result of a 1 - 1.5 day hack by a work placement trainee - treat it nicely :-) The fact it generates a JSON data structure internally which could be uploaded/shared is as much the point as the fact it has 3 micro-tutorials around sequencing, control and selection.

The bracelet was created as follows:

-

Thermoplastic was used at the wristband body - about 5-10g. This is plastic that melts in hot water (above 60 degrees), and becomes very malleable.

-

A number of LEDs and and LDR

- The LEDs connected to the 3 digital pins, A0 and A1, with A2 connected between an LDR and 10K resistor.

-

A DF Robot Beetle - which is a tiny (and cheap ~£4.50) Arduino Leonaro clone - though it's the size of a 10p piece, and only has (easy) access to 6 pins.

-

This was MUCH more fiddly than expected, and there's lots of ways of avoiding that issue. In the end the bracelet was electricly sound, though having access to a soldering iron (or rather a place where soldering could take place) would've been handy. We remarked several times that building the bracelet would've been easier at home multiple times - which I think is a positive statement really.

-

Again the cost part was very simple, and due to time constraints no behaviour of the LDR was implemented. On the upside, it does show how simple these things can be - http://pastebin.com/FzQqGSTv - again howvever, if the microcontroller was tweaked, you could use bluetooth and use something like the iotoy library above - allowing really rich interaction with other devices.

In fact we had a fair amount of this working before the meet the teenagers session. As a result we had concrete things to talk about with the teenagers, who warmed up when we point out the website and devices were the result of just a few hours work.

The feedback we had was really useful and great. This also meant that while physical and tech building continued on the second day, more time could be spent on the business case and audience benefit than might have otherwise - though never as much as you'd like.

Feedback we had was:

- Make it chunky!

- Can you make it velcro-able - so we can attach it to bags, clothing etc as well. ** It also made it more possible to add to things like belt buckles, jackets, hats etc.

- Can you have these devices controllable / communicating?

- Can you make the web app an Android/iOS app?

- Can you add in more sensors?

- Can it be repurposed?

- Call the project DressCode - this is one of those things that is a moment of genius, and so obvious and so appropriate in hindsight.

This instantly solved a problem we had in terms of keeping wristband small and elegant - chunky makes everything alot simpler. Velcro was a good idea, but a but late in our build studio to start over. The idea of controlling and communicating is right up the angle we wanted to pursue (IOT type activities using the iotoy library) but didn't have time for in a 1 - 1.5 day hack.

The idea of having a downloadable app was one that we hadn't considered, but fits right in with the system - after all this would be able to directly interact with a bluetooth wristband, and the communications stack is already written. Having more sensors was obvious, and repurposing made sense if we switched to something using velcro.

It was a really useful session as you can imagine.

The Pitch :: Dress Code

So we carried though to the pitch - DressCode - Fashion of the Tech Generation. (After all, a generation now will be learning how to code behaviours of some kind - so this is a fun application of the skills they'll be learning)

We said in the creative pitch what we'd allow you to do, and said we were allowing you to do just that - as you can see from what our core aspects were vs our prototypes.

Some key aspects of making this work would be the development of kit forms for tech bands which could then be made and sold by 3rd parties and partner - assuming they meet a certain spec.

The ideas behind the pitch included self-expression - the ability to look like the group or different from the group - the ability to share behaviours, to be part of something larger for the coding to be a means of creating behaviours for something but also that it leads naturally into coding for other devices - such as indicator bands or gloves for cyclists, shoes for runners, bottom up fund raising as happens with loom bands, and as a starting project for learning about coding - with a strong/fun inspiration piece involving TV - from headlining glastonbury through to a light up suit for Lenny Henry for comic relief - where each red nose is a seperate pixel to be controlled.

We described the user journey from the TV to the webapp to the techband and back to events and the TV show.

Pitching doesn't come naturally to me - the more outgoing you are in such situations the more likely your idea gains currency with others. Emily led our pitch and I though did a sterling job.

Competition however was very fierce. If our idea doesn't go through, it won't be because it's a bad pitch or a bad idea, it'll just because a different pitch is thought to be stronger/more appropriate for various reasons.

Hindsight

Hindsight is great. It's the stuff you think of after the time you needed it. In particular, one thing we were ask to do - and I think we kinda addressed it - at the build studio was to deal with the link between the techbands and the online web app and TV show. The way we dealt with it there was to decide to make available the same DSL to both wristbands (or blinkenbands as I nicknamed the code) and garments. ie to allow the same behaviour online or on a garment to control a blinkenband and so on.

That's pretty good, but there was a better, simpler solution staring us in the face all along :

-

The felt strips we sewed LEDs onto then wired up with conductive thread, were pretty simple to make. Even sewing in the Beetle would've been pretty simple.

-

Putting velcro onto those would've been simple - meaning each piece of felt could be a blinkenband. Also each blinkenband could be attached inside a garment (as each strip was), allowing at once both more complex behaviours but also a much cleaer link between the wristbands and the garments.

-

Also, attaching bands inside a pre-existing garment also drastically reduced the risk element for teenagers in building a garment - if it didn't look good, you still had wristbands. If it DID work, you gain more kudos. Furthermore, if you did this there's an incentive to make more than one wristband with two side effects - firstly it encourages more experimentation and play - the best way to learn but also leads to people potentially selling them to each other, secondly it encourages people to make more than one - since once they've done one, if they do more they could make an outfit that's all their own.

-

Also, if you did this, you have an activity that while a little pricey (about £10 each all in) it IS the sort of activity a Guides group would do - especially at camp (assuming a pre-programmed microcontroller ) in part because it's a group that tend to do more crafts type activities and would actually find the light useful in this situation. While people have ... "isn't that rather 19th century" ... views of things like Guides/Scouts, they do both cover the target demographic, and out of the two, it seems more likely to get Guides happily making felt/fabric programmable blinkenbands than Scouts - based on who the two sets attract.

For me, it's this final thought that made me think that this would definitely be a good starting point - since it seems a realistic way of connecting with the demographic. (Ironically - getting leaders on board in groups would perhaps be harder work!)

Closing thoughts

All in all, an interesting and useful couple of days, leaving me with some clear ideas of how to take things forward - with or without support from connected studio - which I think makes this a double win. Obviously getting 6-8 weeks to work on this for a pilot would be preferable to trying to cram it into my own time, but to me the Build Studio definitely proved the concept.

As mentioned an actual real world example of this would have to:

- Identify a realistic event

- Make the audience benefit clearer, figure out a marketing strategy

- Build a better/more concrete garment - I started unpicking my jacket, but didn't have time to pixelise it...

- Build a better web app - close the loop to controlling the garment, linking to users

- A downloadable app - which links to the online account for spreading behaviours to a device.

- Better tutorials, and kits for building tech bands.

All in all a great and productive couple of days.

Next up, building robots for the BBC academy to teach basics of coding to BBC Staff (though I suspect they'd like tech bands too :-), but that's another day.

Later edit

(27th August)

Well, this is a later edit, and a shame to mention this, but Dresscode did not make it through the Connected Studio to Pilot. That's the nature of competitive pitching though, which is both sad, and awesome because it means a better idea did go through.

Regarding Dresscode itself, the Connected Studio team also said the following:

With regards to continuing your work on this independently, the idea is your IP and as it did not get taken to pilot the BBC doesn't retain any IP on Dress Code. The only caveat is that the idea cannot be pitched at another Connected Studio event. However, the Connected Studio modus operandi does not replace BBC commissioning, so feel free to progress the idea this way. We must add that if choosing the BBC commissioning route, it's up to you to talk to your line manager about this before any steps are taken.

So while Dresscode as a Connected Studio thing is no more, it could be something I could do independently later. We'll see.

Nesta Report - Legacy of the BBC Micro

May 23, 2012 at 11:21 PM | categories: BBC, programming, reports, nesta, kidscoding | View CommentsEarlier in the year we visited MOSI - which is (these days) a Manchester branch of the Science Museum. Anyhow, one of the long standing exhibits is of the Manchester Baby - or more specifically a restored version of the Baby which has been lovingly restored with many original parts. The Manchester Baby is significant because it was the worlds first stored program computer, and was switched on and ran it's first programs in June 1948.

The exhibition it was in was in a celebration of computing, including the BBC Micro. They had a survey, which would feed into a study on the legacy of the BBC Micro, you popped your answers in and they'd forward you the results if you were interested. I ticked the box, and duely today recieved the following email:

Thank you for responding to the BBC Micro survey that the Science Museum conducted in March 2012. We received 372 responses which is amazing given that the survey was only open for a couple of weeks. Many people left detailed responses about their experiences of using computers in the 1980s and the influence it had on their subsequent careers paths.As you took part in the survey I thought you might be interested to know that the Nesta report on the Legacy of the BBC Micro has been published today and is available to download here: www.nesta.org.uk/bbcmicro

It's an interesting report, and from what I've skim read it seems to be a good report. If I had to pick out one part, the final chapter - "A New Computer Literacy Project ? Lessons and Recommendations" in particular is something I think is very good food for thought, and motivational.

In particular it makes 7 recommendations which I'll aim to summarise:

1. A vision for computer literacy matters

The report singles out John Radcliffe as a single motivating force in the original Computer Literacy Project as being a key driver in the success in the past. it goes on to say:

- Today, there is no single vision holder creating the partnership between industry, education

and the range of actors who want to change things. {...} personal leadership and vision, based on

a level of knowledge and understanding of the industry that inspires respect, and backed up

by significant skills in diplomacy, is vital at this point in time.

I'm not sure I agree on the point of regarding a lack of a vision, but possibly agree on their being no single vision.

2. We need a systemic approach to computer literacy and leadership.

The key points brought out here is that the reason why the CLP worked last time around was due to there being efforts at many levels - all the way from grass roots, all the way to high level government buy in, which included resources and that the key reason for success was the many micro-networks that existed, which were assisted in co-ordination (in part) by the BBC's Broadcasting Support Services. (which I don't think have a modern equivalent) Crucially though, individuals and local groups had to take ownership and did.

It makes two interesting points:

- A key part of this plan will be empowering local and regional bodies to take part and own this new movement for computer literacy. Organisations leading this effort need the commitment, the capability, the skills and the scale to deliver. At present there are many candidates, but no one organisation that meets all these criteria. Someone needs to step up to the plate.

In particular, it then does on to single out the BBC, but with some caveats:

- The BBC may be able to replicate their previous role, by providing supporting television and

online programming, but to deliver at the scale of the original CLP would require not only

significant buy-in at a senior level but significant institutional re-engineering and resources.

This final caveat of buy-in at a senior level, and buy in with resources is an important point. After all, it's one thing for someone to say "this is a good idea" and another for someone to say "yes, this matters, here's resources" - which may only be time and space.

3. Delivering change means reaching homes as well as schools.

While I really like the last part of this recommendation because it really says what should be done clearly and succinctly...

- We need a contemporary media campaign: television programmes that

legitimise an interest in coding, co-ordinated with social media that can

connect learners with opportunities and resources. This is a vital but

supporting role, arguably still best played by the BBC.

... it gets there by making a point a point which I emphatically agree with - that the focus of this must reach out into the home, rather than just into schools. In particular it notes a point I've made repeatedly:

- Despite the BBC Micro now being considered ‘the schools machine’, the computer was actually

more important in its impact of changing the culture of computing in the home, particularly

through the legitimising effect of the television programmes.

The key point brought out is that it's this aspect - which boils down to engaging children in their time - that really matters.

4. There is a need to build networks with education.

Again, the executive summary is nicer/kinder than the final chapter, and in particular calls out a real issue from the BBC side of things:

- At the core of the original CLP were the BBC’s educational liaison officers {...} These two-way networks provided an invaluable way of both listening and delivering appropriate tools and training for adult, continuing and schools education. {...} These days, the BBC has neither the equivalent staff nor the resources to play such a role.

That's pretty harsh. However, it's interesting to note that there are some groups actively looking at improving this sort of thing. I think however there's a long way to go based on what I've seen. There's misunderstanding about how schools work, how academia works, how industry really builds good systems/works, how the BBC operates today, etc.

On a positive note, people are talking, listening and trying to figure out how to move forward - which IMO supports this recommendation.

5. There are lots of potential platforms for creative computing; they need to be open and interoperable.

This point really brings summarises the issue I've described before of "ask a hundred engineers what the BBC Micro of Today would be and you get a 100 different answers". Furthermore though it points out that the reason why the Micro worked was because it helped provide a clear common platform for talking about things.

Today the issue is that we have a collection of micro-development environments which aren't joined up, either in practical terms or conceptually, but if they were more joined up, even in just a conceptual framework for discussing things we could make progress. Without this, it makes the task of teaching this in schools hard, and even harder in the home for someone to say "where do I start?"

It's probably worth noting at this point that there is a project which may result in just such a common platform or framework. It's a project I've helped spec out, and Salford University are hiring someone to work on it. It's target is really to do with "the internet of things", but is spec'd out in terms of pluggable micro-development environments. It's my hope that this could help head towards a common platform spec. We'll see.

6. Kit, clubs and formal learning need to be augmented by support for individual learners; they may be the entrepreneurs of the future.

Again, this reiterates the need for support outside schools and notes that last time round the informal learning was more influential than formal. This relies belies something quite incredible - it succeeded primarily because people found it fun and had sufficient support.

Not only this it specifically points out that these things need to go beyond after-school clubs, and that whilst those are good, these run the risk of following a route of formal learning rather than the motivations that encourage longevity. The former could be said to be "I am doing this because I've been told I should", whereas the real motivator is "I am doing this because it's fun and I want to". I think this is one place where the executive summary is punchier than the main recommendations:

- There is a need for supporting resources that can develop learning about computers outside

the classroom. These may be delivered through online services or social networks, but must

bring learning resources and interaction, not just software and hardware, into the home.

7. We should actively aim to generate economic benefits.

This recommendation points out a handful of things:

- The CLP built upon pre-existing skills in industry

- That this stimulated a market - that boosted that industry

- That that boost also then led to much larger take up that you'd expect otherwise

- That this then drove the industry further down the line

It notes that whilst the third and fourth points may be the goal, that there's real benefits from the second point, and this time around any boost could from international opportunities as well as national and regional, and that including economic benefit is a good idea.

Personally I think that final point is more important than people realise. I still remember to this day hearing about a kid writing a game in his bedroom and getting paid £2000 for it. This was 1982/1983 or so, and that was an absolute fortune from my perspective, and the idea that you could get paid for creating something fun was an astounding thought. So you'd get something fun out of the process. You'd have fun making the thing. And you'd get paid for doing it. A bit like the idea you have tea testers excites people who like tea. You don't get interested in tea because you'll get paid for it, but it's an intriguing thought. Likewise, you don't write code because you'll get a fortune - you probably won't. What you might get to do though is something which is fun that you can live on, because it's outputs are useful to people. That's a pretty neat combination really.

Anyway, I hope the above points have whetted your appetite to read the whole thing - it's an interesting read. Go on. You know you want to.

Hack to the Future (H2DF), Preston, 11/2/12

February 19, 2012 at 05:49 PM | categories: kidscoding | View CommentsLast weekend (11th Feb) I was at Hack to the Future (H2DF) in Preston, organised by Alan O'Donohoe and held at his school - OurLady's High School, Preston. What's that I hear you say ? Well, the blurb for the event was this:

-

What is Hack To The Future?

It is an un-conference that aims to provide young digital creators aged 11 - 18 with positive experiences of computing science and other closely related fields, ensuring that the digital creators of today engage with the digital creators of tomorrow.

We plan to offer a day that will inspire, engage and encourage young digital creators in computing/programming ... -- [ from here, snipped ]

Originally, I'd intended to attend as just someone interested in this area, and perhaps putting on a session (it was an unconferences after all) teaching the basics of something. In the end I helped BBC Learning Innovation in a more official way (ie wearing my BBC id, etc), helping them test out a bunch of ideas, created some tutorials, acted as a mentor/guide on the day, and yes, taught a bunch of people young and old about various aspects of coding.

How the Day Went

In short, brilliantly. Very tiring, very long day, but very rewarding and learnt lots.

After an initial quiet period when everyone was setting up, and they were having welcoming sessions, we started getting a few visitors. They were made to feel welcome, and we chatted about what we were doing, and very quickly kids were sitting at laptops, learning to hack (in many cases) their first bits of code.

There were six laptops in use at any point in time, and we were after that initial start then very busy for the entire day. (Only stopping briefly for lunch) 3 devs who'd worked on the prototype BBC Learning were testing, and a few helpers from BBC Learning and one from BBC Childrens, and myself were all acting as mentors working through the tutorials I wrote as well as the prototype's built in tutorial.

Some learnt to bling up a simple hello-world style web app. (Which you can think of as being like a e-greeting card really) Others extended the quiz with different questions and answers The vast majority I worked with extended the image editor to add a collection of user interface elements, model elements and actual filters for flipping the image, inverting colours, embossing it, brightening it, or changing the HSL values, as well as changing mosaic tile sizes. (These used the Pixastic library)

Given these were done in 20-30 minute chunks by small groups of 1-4 (depending on how many came round), I think this was a great result. Crucially, I think kids took away the fact that you could do this, and that all you need is time, a text editor and a browser (at least for javascript)

As well as the reward of writing some task, each child that attempted it received a BBC Owl Badge, and a BBC Owl cloth patch, and some other bits and bobs.

Primarily because I had the documentation for the Pixastic library open in a browser window on a second desktop, I tended not to use the platform BBC Learning created, choosing to use my laptop instead. The other 5 groups though used the platform all day long, with as much success as I had with the kids.

For the large part, the children were doing the driving - they did the typing, they decided what they would code, how they would code it and why. I purposely stood behind the screen with them in front of the computer, making it clear it was their opportunity. I'd feed some information about code structures - by pointing at code printouts, and then guide by asking questions about "Where do you think X is? How might you add Y? Can you see anything similar to what you're after ?", but otherwise left all the decisions to them.

At the end of the day, some key takeaways for me were:

- Whilst tools are needed, they only need to be sufficient to get started.

- What is far more important is content - tutorials. The more of these that can be written, the better.

- To emphasise this, there were a number of teachers asking for the tutorial materials and asking when/if they could be made available. I'm hoping sooner rather than later. ( Since I wrote them on my own time, I could just publish them, but they'd be less likely to be found if I do that.)

- This need makes perfect sense when you consider that many teachers - especially primary school - are not specialists in coding. A handful may have these skills, but nowhere near all, so there's clearly somewhere support could be given.

- A huge level of demand of interest from children - of all ages - even the very youngest who attended both wanted a go, and also "got it" when walked through.

- An unexpected level of interest from digitally literate adults who want to do the same, BUT with the huge caveat of not having the time/task orientation

- To me, it confirmed that the issue isn't just coding, but in being able to create controlled automation of intellectual tasks. (Akin to Nintendo's focus on "play" and "games" rather than on "gamers")

It made me feel that there is a need for compelling, useful, interesting and sufficiently featureful and sufficiently understandable content, code, examples and metaphors. (My tutorials/examples filled that gap for the day, but there's a genuine wider need) That content can't be written by non-experts but needs to be written or translated perhaps for complete novices.

I'm painfully aware of many many good things being done in this area, but is it reaching those in the teaching profession? My impression, based on reactions I saw, is "not really". There's going to be a variety of needs there I think, both in terms of pulling together existing resources and in terms of creating new resources, but also in terms of getting the resources in the places they need to be.

On this note of "relevant support material", it's perhaps worth noting that I also took along my inspiration for my tutorials - in the form of my collection of kids coding books from the 80's...

This turned out to be quite useful. After all, these days programming languages are generally focussed on giving instructions to computers in ways that make the programmer's life easier. This really means communicating in a way that other developers understand. Being able to show kids books which were kids books back in the day, which actually assumed that teaching machine code was a sensible and plausible thing to do (and it was) really helped in showing them "yes, you can".

For me, this aspect of opening eyes to "yes, you can", and then seeing the light go on in children's eyes when they realised "Yes, I really can! I made it do THAT!" was fantastic.

Adults!

Also, there were a small handful of adults who came in asked "How do you do that ?". I found this both interesting and useful in that I could clearly explain to them, but also learn why they wanted to know. What I've learnt from that encounter could easily take up a whole blog post in itself. However, some key takeaways:

- Whilst kids can spend hours focussed on playing with something - given a good enough motivation, generally speaking adults simply do not have the time to do so.

- Adults need task oriented tutorials, that actually match the tools they have available in practical terms

- Recording a macro as a script for later editting/driving the app may be enough.

- But too many apps don't allow this, or it's inconsistent between apps or difficult to use or even find.

- This task orientation is also more like what happens in a class room where you also don't have time to spare.

- Having the usborne books reminded some "yeah, I remember that, you went 10, 20, 30 and had to leave space for 11,12,13". This means they learnt the ABC's but never had a route to actually use those ABC's.

This makes me think two key points:

- There's potentially also a big need/market for task oriented computational tools among adults. (This helps explain the enduring popularity of spreadsheets despite their problems)

- When talking about computational literacy, it's not just children.

BBC And Hack to the Future

(Caveat: In this bit I'm talking about another part of the BBC, I've probably got something wrong here :-)

If you scan through the list of attendees at Hack to the Future, you'll see a number of attendees there from the BBC, and specifically "Innovations, BBC Learning". This is the bit of the BBC that tries to figure out the things that BBC Learning could commission. ie They try out things BBC Learning could do, see what works, what doesn't and based on all sorts of criteria suggest specific things that BBC Learning could do. They're also the bit of the BBC that asked Keri Facer to explore interest & possibilities.

So, ask a 100 engineers, you get a 100 different answers. Some people thought that a Micro 2.0 would be hardware - either Arduino/mBed/BeagleBone like, RaspberryPi/Tablet/Netbook/Net Top like, a pure webapp, through to downloadable Apps, etc. Unless you try something you won't learn.

So BBC Learning Innovations decided to try something - specifically "can we build a kid friendly IDE that enables them to get started using Javascript & HTML5". Now, Javascript is far from my favourite language, but I can see the logic behind picking the language, and it's both unavoidable and ubiquitous - in a similar way that BASIC was 30 years ago. (Well, things actually, but I'm going to focus on what was taken to H2DF for this post) Heck, faced with a similar problem 14 years ago, I reached similar conclusions.

So, Parmy has been leading a small dev team to test out the idea, and built a very simple IDE by taking Eclipse and either skinning it, removing chunks of functionality, or rebuilding from constiuent components (not sure which approach :-). The upshot is one idea of what a BBC Micro 2.0 could look like. However, it IS a testable, concrete, real thing that you can put in front of kids and see if it helps.

Someone reading this is likely react to any/all of the decisions in various ways... but as I've said privately: it's a typical geeky thing to go "how can I improve this hammer that I have?" which I think is a good reaction, but I really don't want to overshadow the "We've got a Hammer! We've got a Hammer! And we can do This! and This! and This! " thing that is going on. . (Once you have a hammer, you can see what you can do with it and whether you want that, a nail gun or screwdriver :-)

What did this platform actually look like though? Well, I happen to have a screen grab from a screen cast created by Parmy, which I feel no qualms copying here since it was demonstrated to dozens of people at Hack to the Future:

Hack to the Future's organisation was happening concurrently with this, and it looked like a pre-pre-pre-pre-pre-alpha version of the codebase would be ready for the event, so the BBC Learning Innovations team decided to take the platform to H2DF to try it out. My understanding of the plan behind this was:

- Inspire, engage and encourage young digital creators in computing/programming

- Take the downloadable platform there and see whether kids could use it

- What's the level of interest from kids, teachers, and professionals ?

- Was that sort of platform a good idea ?

- Should it be a downloadable app?

- What's missing?

- Is this even a good idea ?

- etc.

ie all lots of very good reasons.

I think the day also went a very long way to achieving either the goals, or answers to the questions listed above.

Like any time you take a new piece of code on the road, there were teething issues:

- Power was at the side of the room, so rearrangement of the room was a clear necessity

- The tutorials assumed a working network connection, and the school's wifi was too locked down

- The platform's codebase was very much pre-pre-pre alpha, ready only days before the event. Whilst for basic "hello world" tutorials it worked one way (which I expected), it worked a very different (more eclipse like) way for non-hello world tutorials. This threw me somewhat - I use Kate and commandline tools normally. (Parmy and 2 other devs who'd been working on the codebase were there as mentors as well, so this was fine for them :-)

- When I did use the platform I found it worked, but a little rough around the edges. For example it currently masks errors. I'd flagged this up before, but I guess there hadn't been time to resolve this before the day.

(Given this, you could ask, "why take such pre-ready code on the road?", the answer of course being it was a priceless opportunity to answer the questions above)

I pondered whether to list these, and then figured a warts and all thing was a good idea, primarily because mentioning warts makes it easier for everyone to avoid them in future.

What I did in prep for H2DF

As background, I've been recently trying to figure out how BBC R&D (the dept I work for) can help BBC Learning with their goals (BBC R&D's job, in short, is to support the R&D needs of the full spectrum of what the BBC does). So on a limited time basis I've been spending time with them, and helping out however I can. After all, IMO, first step to anticipating someone's needs is to understand them and their goals, and mucking in is one way to learn that :-)

In this case, it struck me that the best way I could help out with testing the ideas was to:

- Help out on the day as a mentor

- Write tutorials & cribsheets

- Provide a mental model about how to teach building basic browser/client side based web apps.

So I wrote 2 tutorials:

- A javascript based quiz, using a little bit of jquery to download the quiz and update the screen

- The other was a simple image editor/manipulator using the pixastic library to pull in filters.

My aims for these tutorials were:

- To be sufficiently interesting/useful to be engaging.

- To be sufficiently simple to be comprehensible by kids who'd never coded in a very short time period. (Each session was to last 20 minutes)

- To be also sufficiently clear to be able to be modified by kids

- To make it clear that it was possible to do so, and that the modifications reflected "real" coding

- To be no more than around 100 lines long, including HTML, style sheets, and javascript.

- For each to teach a basic structural principle by example. Eg

- The quiz demonstrated a data driven game engine, obtained by an ajax call, with a staged user interface

- The image editor really demonstrated how to add user interface elements dynamically, how (and why) maintaining a model of the user interface was a good idea, and how to interact with library of functions.

- Both were designed to show common structural elements common to client side based web apps.

This is a trickier balance than it might seem, and both took a procedural view of coding rather than object oriented approach. (Once you've demonstrated the value of having a model, I think you have better justification from the learner's perspective for increasing the code complexity in favour of flexibility)

The reason I took this approach is, in addition the the old Usborne books, probably attributable to Dave Hunt of the pragmatic programmers. There's a great book he wrote called "Pragmatic Thinking and Learning" which describes lots of learning models. One of them is called the Dreyfus Model of Skill Aquisition, which has 5 levels:

- Novice - Follows Recipes

- Advanced beginner - Adapts Recipes

- Competent - Understand when recipes don't work, can plan their own

- Proficient - Want the big picture, self correct and self improve, understand context (why you don't do that ?!)

- Expert - As well as all above, work from intuition. eg "I think X has this illness, I'll run these tests". This is the inverse of earlier levels of skill.

The key point really, is that many computing books are really focussed on competent and proficient and very few on the true novice. By contrast if you look at the old Usborne books, they they were packed with what are effectively recipes. In part this is also why I picked the Pixastic library - its documentation is entirely geared towards the novice or advanced beginner.

If you're writing documentation or tutorials, I really think you should be thinking "which level am I targetting?" and "am I addressing the boundary - how do I enable someone to leap from one level to the next?". Clearly on Saturday though I was targetting Novices, and enabling to jump over the first hurdle of "I can't" to "I can".

So, along with writing the code, I produced A3 PDF's describing, in the style of those old Usborne books, what the code did and why. These were deliberately that size to encourage readability by groups, and used friendly fonts :-) Sadly, I didn't have time for little hand-drawn robots or manga cats. (I think using manga cats would be more gender neutral :-)

I'll probably blog about the analogy I used on the day for web apps at a later point in time.

Where Next ?

What BBC Learning do next is very much up to them, and I'll support them in their plans.

This whole event though did get me thinking about Micro Development Environments - MDE's - as opposed to Integrated Development Environments (IDEs).

- The platform we had was a micro development environment for javascript based apps

- The Arduino development environment is a micro development environment for a particular type of embedded system

- Microsoft's Gadgeteer platform is another, for a similar type of system. Microsoft's Kodu, again, is another with a different focus.

- Rapsberry Pi, has the possibility of being either a micro dev environment, or as a host environment.

- Yousrc is a flash based / basic like language for creating web embedded games and similar, again a micro dev environment.

- Scratch, is another.

- Play My Code, is again, another Micro Development Environment, targetted at making it fun to write games for the browser. Personally I think Play My Code falls into the category of "most likely to hook kids and those who are kids at heart". Really neat :-)

- And so on.

In essence there are a growing number of Micro Development Environments, and each focusses (rightly) on a particular domain and has its own strengths. Personally, I think "there next", along with tutorials focussed on the different micro dev environments, and perhaps looking at "what micro dev environment is missing?".

Since H2DF I've spent, a couple of evenings in the past week I've tried knocking up what could be a web version of the BBC platform, incidentally, since it looked like a reasonably plausible thing to do, and I think this looks pretty nice as a possible browser based dev platform:

That allows you to load 2 different apps, and the source for the MDE, edit them, and run them. (No saving, but you could copy and paste to a local editor). The fun thing is that as well as running on my laptop that it runs on a Kindle and even in my (non-iOS, non-android) phone's browser. There are downsides to this approach, but does no-download outweigh that as well?

Early days to say the least for that anyway, and more for a blog post another day.

Thanking Alan, AKA The Perils of Hoaxing

My closing note is really to thank the irrepressible Alan O'Donohoe for organising this Stone Soup. If he hadn't hoaxed everyone at Barcamp Media City and again at Pycon UK, then it's very likely that certain reports around H2DF wouldn't've been taken as a hoax as well. I think the lesson there is do it once, and make sure everyone understands it was a hoax and why, and people will be happy. Do it twice, and when something happens that sounds the same then it might be assumed to be a hoax. I think that's a real shame because what he organised really was amazing, and hopefully people will forgive him the hoaxes now :-)

Also, whilst I thought the hoaxes were a bad idea, but the more I heard about the detail he went to - setting up stooges in his audience for example, the more I can't help but admire the audacity. I don't agree with it, but I can't doubt Alan's determination, impishness, and element of wanting to bring fun to the table.

So many thanks to Alan for organising H2DF, it was lots of fun, we all learnt lots both adults and especially the kids :-)

Yes, he cried "The BBC at my school!" twice, but the third time, yes, the BBC really did go to his school and like many others there, I wish we'd had an IT/Computing teacher like him when I was at school ;-)

Continuity

I'm painfully aware that I haven't really followed up on my last blog post about "what I'm actually going to do", but rather been "doing it". This is probably a good way round, and my next post will pick up from the last. ex-Scout's honour. :-)

This is also because a fair chunk of what I was planning has been done by the Play My Code team. Go take a good look and play with their site.

Replicate the past - the cause, the mechanism, or the effect?

October 23, 2011 at 05:17 PM | categories: kidscoding | View Comments

Meta: The next post in this category after this will be "what do I plan to do". I'll keep this post brief, unlike the last one. Sorry for the length last time, still finding my feet.

Recap: I've so far argued that part of the cause of kids starting to code in the 80's was really a catalytic effect in legtimising coding as an activity that yes, kids can do, leading to the creation of many books, tools (micros), and so on being created as part of a wider ecosystem enabling children to learn.

Replicating Mechanisms?

The thing is, it's worth remembering that these were mechanisms, and mechanisms legitimate at the time. As a result, this is kind my issue with Raspberry Pi. Now again, I don't want to do a downer on Raspberry Pi - it's a fun idea, and it has a lot of geeks excited. I've yet to hear anything to excite a child about it. Me ? Yes, I'd love to have one. I've got some grippers (along with associated servos etc) from my birthday, along with a few faraduino's and a tracker robot (which I had previously - in part because of building a catastrophene for my daughter) which would really nice to control with an onboard diddy computer. However, I doubt the tech savvy kid of today - who own a display with an HDMI input... - would be excited by it. (I'd love to be proved wrong on that though :-)

However, it assumes that the majority of kids don't have access to hardware they can code on. This is despite broadband takeup in the UK being at the 74% , and higher in households with children at 91% overall. ( OFCOM ) Any household with a browser, let alone broadband, has sufficient hardware to start coding. As a result, I don't think hardware is really the problem to attack.

Put succinctly, I think Raspberry Pi is replicating one of the mechanisms of the 80s, rather than the cause or the effect. This doesn't make it bad, but neither does it mean it's inherently good. It means it's a tool, which may have an effect. But despite its price, it's not cheaper than a PC donated from Tesco vouchers or Sainsbury vouchers (etc).

I can't see the kids being interested though - so by itself, it doesn't help me as an interested father...

Replicating Effect?

This is what lots of people are crying out for. For lots of different reasons. In order to replicate the effect, we need to examine the cause to reinvent new, more appropriate mechanisms for today. To do that, we need to do two things:

- Look at the motivations of the past and especially of people today - the causes that did it last time ? What will make people do things today? Are they different ? How have things changed ?

- Look at the ecosystem of the past, and the ecosystem of today.

If we simply replicate mechanics, albeit in an interesting and cheap way, we risk doing the equivalent of putting a typewriter in a living room and expecting that to be the way that children learn to type.

Replicating Cause?

I've looked at causes in previous posts, so here I'll summarise. People making micros wanted to sell them, saw children as key users, and made hardware affordable. The governments of the time seeing needs of UK industry to have a technologically skilled workforce. Arcade games (and similar) were growing in popularity and micros allowed this at home. Kids wanted to play games and share them with their friends. They wanted these games either very cheaply or free - through typing games in, finding and correcting bugs, and taping them. This also led naturally to customisation, new games and selling tapes. A fledgling games industry was burgeoning, and seen by kids as both fun and doable .

The UK had just had economic problems in the 70s which continued in the 80s. Parents, like always, were looking at "what's best for my child". Parents could see that this was a means of getting their children a better livelihood than themselves. (cf survery on page 11 of the computer literacy project report "pdf"). Teaching children about computers became clear as something which was considered a "Good Thing", and due to internal and external factors the BBC formed the Computer Literacy Project which legitimised this in the eyes of many.

I hope that's a fair summary, but it still misses 2 vital points:

- It was within the reach of children, using tools made available to them, to write games, etc they could share with their friends, in terms of financial, technical, factors social, with educational support through media, schools, books and peers.

- They had few legal ways of getting new games for free, or next to free, without writing code.

Barriers to Overcome

The interesting thing here to me is that whilst the following are all still true...

- Children still seen as a key market, government interest, industry interest, games at home are played by kids and adults, kids still want to play, make up games, share games, strong presence in games industry, UK having economic woes, parents wanting best for kids, interest both within/without the BBC for BBC to do "something".

... I'm not really sure that the other points are still true, for a variety of reasons.

- Parents do not see value (or as much value) in children learning how to really unlock the potential of the power they have available.

- Children can get at an almost infinite library of new games for free, thanks to the existence of the web, and the many systems they use. Examples include fronter), (purple mash ) , club penguin , moshi monsters etc. (the last 2 use a freemium model and allow kids to play together)

- It is not realistically within the reach of the average child to replicate such games of similar power, without jumping over hurdles they may not be able, allowed or willing to jump over.

- Making games and sharing them is not seen as something doable. Let alone the idea (say) of making a game to sell at a school fete.

- It's not seen as fun by kids. (or most adults) I wonder how many adults view games consoles as computers.

- Kids are less likely to pick up a book to discover how to write code because a) those books no longer consider children a valid audience b) publishers don't get bookshops to stock such books c) libraries don't stock them d) kids would prefer to look at a webpage than a book anyway.

I personally think point 5 is a consequence of the way computers are used in schools today, and their usage is taught. Similarly a generation of people brought up to think that computers are things you browse the web, run word processors on, write spreadsheets on, and that's really the limit of their experience I think leads to number 1.

The fact that point 2 exists now also is a psychological barrier between the gratification now (play and chat) vs gratification potentially much later (make, play, chat). Even if they do overcome that barrier, the toolsets available to kids hit other barriers. Many parents see computers complexity as beyond them, the idea of risking the kid "breaking it", is quite frightening. (unlike the switch it off/on again of micros) There's risks from virii, and so on. This means that even if they're willing or able to jump over the hurdles of installing python, scratch, ruby, or similar they may not be allowed to do so (3). Then, even if they do jump over, they do so without any real support, this is in part due to point 6, but also due to the underlying problems that causes point 6.

Finally, the steps necessary (say) for a kid to be able to run an arcade at a school fete and sell games there (I'm sorry, I remember that happening in primary schools in the 80's) is now considered sooo far out of their reach, it wouldn't even be considered possible.

Turning this around

I think in order to turn this around, we need to re-examine the issues and opportunities that are in hand. One of these is that the computers available to kids today are more powerful than the supercomputers of 30 years ago. Another is the fact that kids are reading much more today than they used to (thanks to the web).

These include:

- Educating parents of the value of computational thinking, and unlocking the power of the computers in their lives for their children's benefit. This to parents means not just freedom, but financial freedom.

- Working with the fact that the web is the cheapest/easiest way of getting games and interacting with others. Working with the eco-system that they love today, including the club penguin, moshi monsters, cbeebies games, titter/mary.coms, and so on of the world today.

- Making it realistically within the reach of children today to build, and share games and apps with their friends. Not only in practice, but also in perception, despite barriers of changing the local device.

- Make it seem plausible to children and parents. Something they can do. Something that they can make a better life for themselves doing.

- Making it fun once again. Learning lessons from things like Horrible Histories, etc about how to make "non-fun" subjects fun once again is a real opportunity.

- Recognising that even if books did cover these things (and they should), that the role of books for many kids is taken by web pages today. Books were just a mechanism. (Much as I love books!)

All of this has to be done whilst at the same time:

- Respecting the freedom of children whilst they're doing this

- Recognising that the internet is here to stay

- Not assuming that any one group or company, will achieve the goals by themselves.

- Enabling kids to share their creations with others, and have them portable between companies. (code and data portability)

- Recognising that this is happening in a computer literate world.

- Fitting in with the modern approach of cross curricular teaching. (Much like the project/theme oriented schemes of the IPC )

- Taking into account the modern world and where it will be in 2-5 years time, not where we were 30 years ago.

- Recognising that much of computational thinking is of benefit beyond coding and is really problem solving skills

After all, the world of 30 years ago looks as old and archaic to the children of today as 1955 did to Marty McFly.

My next post in this category will describe what I plan to do. I'd like for it to be a part of the day job at work, but I'd be surpised. We'll see though. However, I have a strong motivation to do this at home anyway, and the ability to do it there too (albeit taking significantly longer), so I'll still be doing it :-)

In the meantime, any feedback on "turning it around" would be welcome :-)

Why did coding at school level disappear ?

October 18, 2011 at 11:11 PM | categories: kidscoding | View CommentsAs before, this post covers a fair range of points, I hope, intended to support my summary. If you just want though, you can skip to the summary.

In my earlier post Children and Computers I was outlined some of the key issues relating to kids and coding. There were 2 points I specifically mentioned that I think deserve dealing with first.

- Why did kids in the 80's really start coding?

- Why did coding drop off the curriculum ? Why was there a change from "Computer Studies" being about building things (~'88/89) to being about using computers ?

The first of these two I've already written about, and had some great responses. This post is about the second. I don't think anyone can claim to have absolute truth in these matters, since the UK educational system is not 100% homogenous. (Indeed, they still have the archaic divisive system of grammar schools and eleven plus in this area). However, I'm trying to describe things as I saw them both at the time and with the benefit of hindsight.

So, why did coding disappear at school level? Is that even the right question? Not really, so let's ask a better question : Why was 'computer studies' replaced with 'IT' ?

Where we left off

In my previous post I was talking about the early eighties - primarily when I was in the juniors at primary school. In days gone by that was called years 3 and 4 of junior school, these days it'd be called years 5 and 6. I talked in a lot about the environment that led to it being socially acceptable, and pragmatically beneficial for even a low income family to consider owning a micro. I summed up there one of the main reasons why kids learnt to code as being - access to free software (Free as in gratis for those who get antsy about definitions).

Again, like many things, at least many things were happening at once.

- The BBC Computer Literacy project was in its hey day. Computers were going into family homes and schools. Programmes were inspiring people as to the possibilities these devices could provide - both on BBC and ITV. Interestingly, the BBC focussed on the less commercial aspects of computers, whereas ITV focussed on games. Both were complementary.

- In schools, they started grappling with what they could do with computers in schools : how best assist with teaching. There was very little software for these machines, so usage was influenced by people like Seymour Papert, and in particular things like Logo. Whilst by today's standards, those micros were less capable than the arduino's and similar of today, they were also as powerful as the sort of computers that put people into space.

- Programmes like The Great Egg Race were on TV (76-86 or so) - invention was part of the psyche of the time, and celebrated.

- In homes, parents saw the opportunity for micros to give their children the opportunity for a better, well paid, job when they grew up. Bear in mind that this was a time of recession, after the recessions of the 70s, and millions of people unemployed. The idea that any kid could write a game and make a fortune from their expertise was something that inspired kids and adults alike. I suspect that most kids really thought "wow", whereas adults (used to longer term planning :-) saw the potential.

- Kids saw the opportunity for free games to play with their friends.

- Games were distributed on tapes which could be copied even at home

That's a pretty heady mix. Out of this, lots of kids learnt to write games to play with their friends, that people like their friends would be willing to buy, which led to success stories and a virtuous circle.

I want to argue here that this industry, this legacy is a side effect of the law of unintended consequences . Consequences of clear intention: let's educate the population to be computer literate. It's a fantastic legacy, but one that when the literacy project was started doesn't appear to have been an initial aim - they planned to make a 10 part series targetted at adults initially and weren't sure as late as 1981 who the audience would really be, and were thinking of targetting an even more niche audience. It's also also a consequence of all the other things that were clearly going on too.

Schools

So let's get into schools. This really means 2 things:

- Computers and computing as a subject worth learning and in need of teaching

- Computers as a tool for teaching and enabling learning.

These are two very different activities. The latter is where the bulk of the rest of this post follows, the former is an idea that really was ahead of it's time. Some people, even then had been way ahead of everyone else. For those who like me like books, even today, there's a great book with a terrible title - The New Media Reader. It has many seminal papers and extracts of seminal books. One of these is an excerpt of a book by Seymour Papert : Mindstorms Children, Computers and Powerful Ideas. This book was published in 1980 which itself seems early, but to give you a flavour of what it's like:

In the LOGO environment the relationship is reversed: The child, even at preschool ages, is in control: The child programs the computer. And in teaching the computer how to think, children embark on an exploration about how they themselves think..

...

This powerful image of child as epistemologist caught my imagination while I was working with Piaget. In 1964, after 5 years at Piaget's Centre for Genetic Epistemology in Geneva, I came away impressed by his way of looking at children as active builders of their own intellectual structures..

...

when a child learns to program, the process of learning is transformed. It becomes more active and self-directed. In particular, the knowledge is acquired for a recognizable personal purpose. The child does something with it. The new knowledge is a source of power and is experienced as such from the moment it begins to form in the child's mind.

Seen in this light, LOGO was always really designed to support the latter point of being a tool for enabling learning, but was mis-categorised by many as learning about computers and how they work. In practical terms, yes, it fits both categories, and yes, by definition by help with teaching 'computers' as a subject, but it also explains longevity - it is 44 years old, having been created in 1967. Yep, Seymour Papert was interested in teaching children using computers before man had stepped on the moon, when the vast majority of computers still used punch cards to be programmed.